From ‘Devotions upon Emergent Occasions’, John Donne

From ‘Devotions upon Emergent Occasions’, John Donne

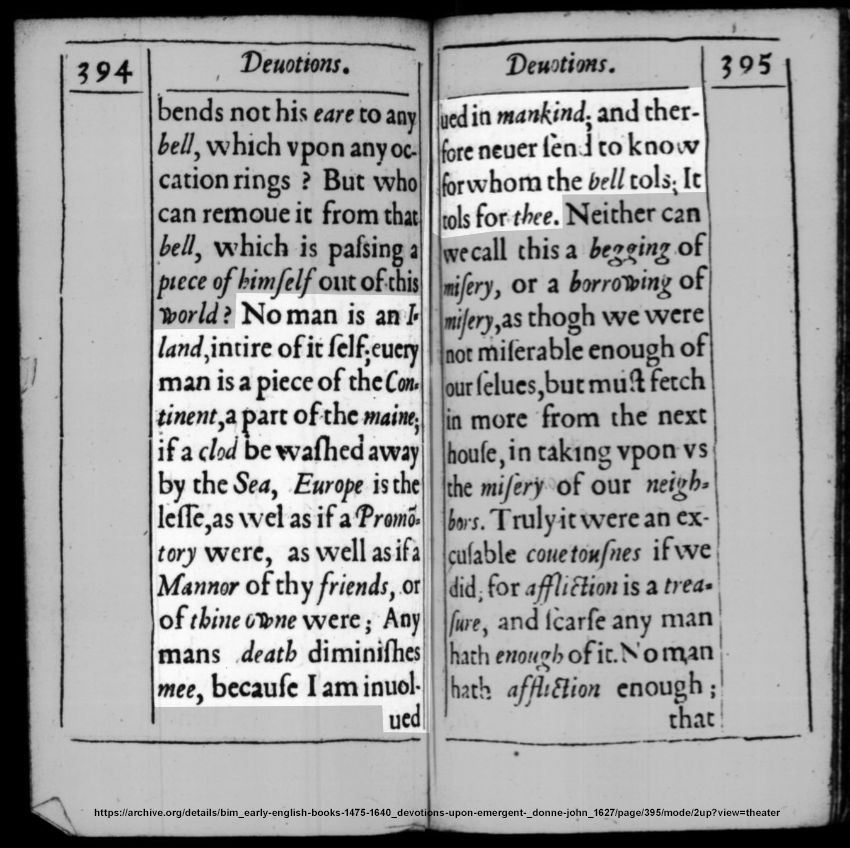

No man is an Iland, intire of itself; every man is a piece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a clod be washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as wel as if a Promontory were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends, or of thine owne were; Any mans death diminishes mee, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tols; It tols for thee.

John Donne, 1624

John Donne by Isaac Oliver, 1621

John Donne by Isaac Oliver, 1621

Written as part of a reflection on Donne’s serious illness and subsequent recovery in 1624. Part of the second to last line was used by Ernest Hemingway for his 1940 novel on the Spanish Civil War, ‘For whom the bell tolls’

You can read a scanned version of a 17th century printing of Donne’s work on Archive.org. Notice the differences in spelling and punctuation, ‘wel’ and ‘well’ on two consecutive lines! In the image above you’ll also notice the ‘long s’ — looks a bit like an ‘f’ — that was common until the early 19th century, especially to write words with a ‘double s’, eg ‘possess’ → ‘’poſseſs’. In the book shown above it’s also used in some initial positions — ſelf — and where the s combines with some other letter to make a different sound, eg ‘waſhed’. Looks the only rule for this printer was, there are no ruleſ — take a look at the use of ‘u’ and ‘v’!!

Map Maker Tool

Essay Writing Top Tips

Introduction (TOPIC - explain what you are going to do) (BODY - do what you said you were going to do) First body para Second body para Third body

Map Maker Tool

Essay Writing Top Tips

Introduction (TOPIC - explain what you are going to do) (BODY - do what you said you were going to do) First body para Second body para Third body